Preamble

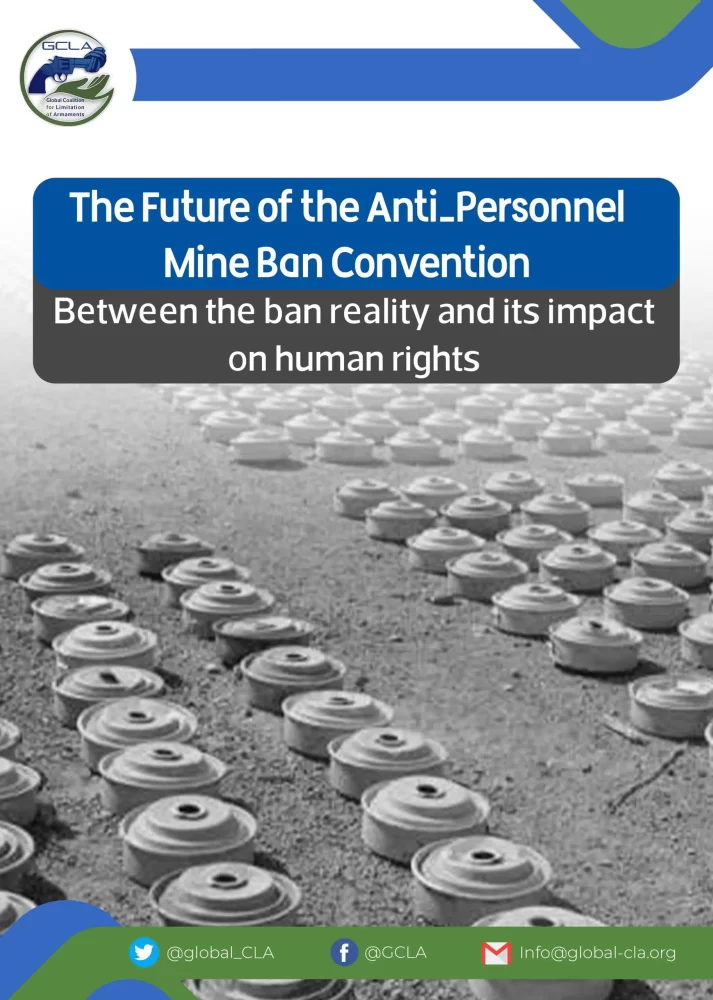

Millions of landmines were planted decades ago all over the world in various places, including Cambodia, Mozambique, Angola and Afghanistan. These landmines have killed thousands and changed the lives of thousands of others forever. Mines, explosive remnants of war and improvised explosive devices threaten the lives of some of the most vulnerable people in society, such as women, farmers, children and humanitarian aid workers who are in desperate need.

Landmine survivors also often suffer from a permanent disability with severe social, psychological and economic consequences. In addition to the direct impact on the people killed or injured, the victim’s family members are also affected, especially if the family is the breadwinner. Members of mine-affected communities are paying a heavy price as they lose their livelihoods, cannot access fields and suffer economic disruption. Landmines and unexploded ordnance are also global problems, but it is difficult to measure their exact size. No one knows the real number of mines laid, the number of people affected thereby, or the size of the areas infested.

Based on this threat, civil society demanded in the early 1990s that the United Nations need to work towards developing a global legal mechanism against the use of anti-personnel mines, which led to the adoption of the Mine Ban Convention in 1997 and other basic texts. Today, many countries have completely eliminated mines, and others are on their way to doing so. The United Nations also works with national authorities, international and regional organizations, and in partnership with non-governmental organizations and the private sector, to reduce the humanitarian, social and economic threats posed by landmines and explosive remnants of war.